By TREVOR GLYNN

SANTA ROSA HIGH SCHOOL, 14, FRESHMAN

I have a geometry class in which I correct my homework from the preceding day, am given brief instruction on the next lesson and then assigned my homework for the day. The cycle repeats itself, day after day.

For me, this is normal. Most teachers center their entire lesson plans on work that students do when not in school. Students, in turn, center their lives on the work that they are assigned. Too many people think that is acceptable.

My geometry teacher spends — as do countless other teachers — maybe 20 minutes of her precious class time doing homework-related things. The 20 minutes normally includes about 5 to 10 minutes of having students correct their work from the previous night. The rest of the time gives students a head start on newly assigned work. As class winds down, my teacher pressures students to individually stand, walk to her and ask her a question about a difficult problem.

That is the point at which I, along with Sara Bennett, co-author of the book “The Case Against Homework,” take issue.

Says Bennett: “Homework wastes a lot of time. Teachers have to assign it, collect it, grade it. Teachers who don’t assign homework report that they have fewer conflict with their students, that their students are more eager to learn, that their students do as well (or sometimes better) on standardized tests and their classes are more engaging.”

The time that is spent having students do various calculations by themselves can be spent doing in-depth problems in front of the whole class. Bennett’s description of a homework-free class seems like a vast improvement from the dull, gray and, unfortunately, factual, stereotypical math class.

So why is homework even assigned in the first place? It seems teachers have their students work at home only because it’s traditional.

“Unfortunately, teachers don’t learn about homework in their teacher training courses, so what they think, and what the research shows, are contradictory,” is Bennett’s way of summing it up.

What teachers do seem to think is that homework teaches children responsibility and helps them to review concepts learned in class. The problem with that idea is that it is without any solid evidence to support it.

“There is no evidence that any amount of homework improves the academic performance of element

ary students,” according to Harris Cooper, a leading homework researcher and a professor at Duke University.

An even greater setback? Those hours doing homework may even have hurt some students’ test scores. Cooper concluded from his studies that a child should receive a maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level per night. That adds up to only one hour of work for a sixth grader and up to two hours of work for a high school senior.

When a sample of 200 Santa Rosa High School students were polled, about 24.5 percent said they got an average of more than two hours of homework a night, and about half said they received at least two — the amount recommended only for seniors.

It would appear the 10-minute rule stands up to statistics, as 60 percent of students said they were given “too much” homework by a single teacher within 30 days of being surveyed.

So what can an excess of homework mean for SRHS students — other than lower test scores?

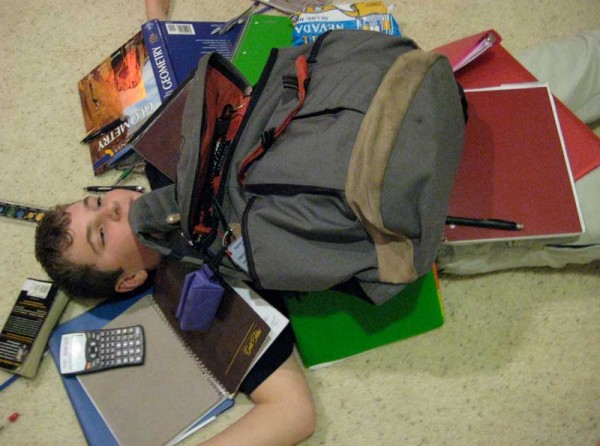

A 2006 poll by the National Sleep Foundation found 80 percent of teens fail to get the recommended amount of sleep. The American Psychological Association found there are more child psychiatric patients today than in the 1950s. According to the Institute for Social Research, there has been a 28 percent drop in the time 15- to 17-year-olds spend playing sports.

These statistics are unified under one single fact: Homework is on the rise. The University of Michigan, which conducted a study of 2,900 students, found the modern student spends 51 percent more time on homework than in 1981.

“The Myth About Homework,” an article on Time magazine’s Web site, says “students ages 6 to 8 did an average of 52 minutes of homework a week in 1981, (but) they were toiling 128 minutes weekly by 1997. And that’s before No Child Left Behind kicked in.”

Bennett says of the strain homework puts on students: “Homework interferes with students’ time to pursue their own interests, play or hang out with friends, sleep, eat dinner with their families, do chores, etc.”

To find out if that is really true, SRHS students were asked not only if homework recently forced them to take time away from hobbies or extracurricular activities, but also if they have, in the school year so far, saved time by lowering the quality of their work. Sixty-six percent and 68 percent, respectively, of students responded yes.

Harris Cooper already proved that overloading students with homework may lower test scores, but not only test scores are hurt. An SRHS student with a poor grade in math class attributes his bad grades to the huge amount of work he is given daily. In addition to work assigned in school, he also has several chores he completes daily. The combined amounts of work he has take him from 3:30 to 7:30 p.m. — four hours total.

“Some days I have too much stuff to even focus on the homework,” he said. “That’s why sometimes it’s not completed all the way.”

What this demonstrates is one of the most troubling aspects of homework: it treats students equally. If there’s anything that every educator should know, it’s that every student is different. While two individuals may have the same ability in a subject, they may differ in a number of other areas.

The solution to this problem isn’t to personalize homework (there aren’t nearly enough hours in the day). Rather, the solution is to eliminate it.

What students tell us and what research shows is that taking such a course of action would do so much for the student as well as the class. The prospect of creating more in-depth and enriching classrooms alone is reason enough to consider a no-homework policy. Once the innumerable independent advantages — some of which are far-reaching enough to affect students’ sleeping habits or stress levels — are factored in, the decision to eliminate homework becomes a no-brainer.